Don't Sell Yourself Down the River

Learning how to float. Huckleberry Finn. People who betray art and themselves. Digital Prisons. Hell is our phones? We deserve better.

During his commencement speech at Kenyon College in 2005, David Foster Wallace led with what he admitted was a “didactic parable-istic” sort of fable. In his story, two young fish are swimming when they approach an older fish. The older fish stops, smiles, and says “Good morning boys, how’s the water?” The two young fish keep swimming along until one looks at the other and says, “What the hell is water?”

Wallace reassured the graduates that he wouldn’t pretend to be the wise old fish who knows what water is. Far from it. “The point of the fish story is merely that the most obvious, important realities are often the ones that are the hardest to see and talk about. Stated of course as an English sentence, this is a banal platitude. But the fact is is that in the day to day trenches of adult existence, banal platitudes can have a life or death importance.”

One such platitude is ‘sink, or swim’. This is mostly used to warn about the perils of not ‘making it’ in the land-based world of school, jobs, side-hustles. A banal platitude, but also one with physical life or death importance when you’re in the water. Just ask the pour souls who hitched a ride on the Titanic. Or the crew of the Edmund Fitzgerald. Or any of the tens of thousands of people who have drowned in the Mediterranean Sea in their search for freedom.

If I wanted to grapple with the importance of this platitude here in New York, I wouldn’t have to travel far. In 1904 a steamboat full of 1,300 Lutheran parishioners travelled up the East River on a weekend vacation cruise. When the boat reached my part of Queens, a fire broke out on the deck. Attempting to escape the flames, people grabbed their life-jackets and jumped for the water. But instead they began to drown. The cork that was supposed to give the jackets buoyancy had rotted and turned to dust. The women and the children who were wearing their Sunday best were dragged down by their stockings and corsets. Of 1,300 people only a little over two hundred survived. It was the deadliest disaster in New York City until 9/11. The steamboat smoked from the bottom of a river that was only 35 feet deep. For days, bodies washed up on the shores of Randalls Island and Astoria, on the same stretch of shoreline where I go to watch the geese float along the water, and where I listen to the waves tumble over the thousands of shards of beach glass that have come to rest on the banks of the river.

⁂

Here is a different belabored parable. On the third day of creation God made the ocean, and later all of the wonderful creatures in it. After getting around to creating humankind in their image, God realized that people had no easy way of seeing the beautiful creatures in the sea. So, God sat at a great workbench in the sky, and decided to make it so that people could be cast into the water. God made some of us fishing rods, others as lines or reels. Many of the people became all sorts of different lures and hooks, or tackles with sparkly fur and multicolored stripes painted across the belly. Some were given the gift of being bobbers, allowed to spend their lives floating along the surface. And then there were weights, some the size of pinheads, others the heft of rocks and small boulders. God was pretty glad of the work, and on the seventh day God closed up shop and decided to go fishing. God staked the poles, and cast out the lines, but for some reason didn’t tell the people what role in the great fishing trip they played. So all their lives people dangle in the water, wondering what they are, and even when they get close to figuring things out, they fall into jealousy. The line wonders why it can’t be the rod, the tackle why they can’t be the line, the bobber why it can’t be a hook, and then of course there’s the metal weight who looks up and wonders why it can’t effortlessly float.

⁂

In the great tacklebox of life, I like to think of myself as a weight. I’m completely alright with it, generally, but then there are these moments where I look around and wonder why I can’t be light and airy. If you need someone to dive into the water, I’m your person: throw in some car keys into the deep end, and I’ll be entertained for hours. But for the life of me I’ve never been able to float.

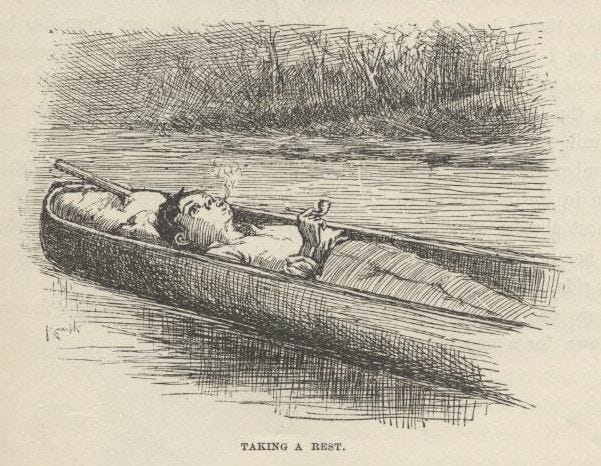

At first, I started to joke that this summer was going to be exclusively for learning how to float. Floating Boy Finds Heaven Summer. But then it became serious. I enlisted one of my friends, J, for this mission. She’s been way too good of a sport about it. We go to the local public outdoor pool. It’s a massive concrete behemoth of a place, with nearly a thousand lockers. From the pool you can see two bridges and a peek of the East River. We started our ‘lessons’ in the shallowest end. It began with watching J float. She lightly lifts her legs, sprawls her arms out. It looks like she’s nailed to an invisible cross. And when she decides she’s done, she folds up her body so that only her head is visible. Then she blows a trail of bubbles in my direction, just for good measure.

I always ask her how she does it, and how she makes it seem all effortless, and she responds with something like ‘Oh just try it.’ So I stick my legs out, and keep my arms out all flat, and imagine that I’m floating on a piece of driftwood. Immediately I start to sink. My body bends like the hinge of a foldout table. For some reason, it’s the ass that sinks first. The rest of the body follows. My legs stick out of the water like the stern of the Titanic. ‘Gentlemen, it has been a privilege playing with you tonight’, while the world’s smallest violins play for me. J says, ‘maybe just try it like this,’ and then she somehow makes it look even less challenging than before. Being instructed by a master of the craft when you’re a strict beginner is maddening. Imagine Van Gogh telling a child working on fingerpaints that she just needs to ‘hear’ the color yellow. In the pool I am a toddler, and I have not even graduated to drawing stick figures.

I tell her, well, maybe I’m just defective. She laughs and we get to move on to easier things than floating, which was a goal of mine all along. We watch the kids chase each other in the fountains, the orange lifeguards lazily blow their whistles, the young couples pressed together in the adult section of the pool. It is all so peaceful and lovely, but I’m feeling none of it. I am annoyed, and grumpy, and slightly humiliated – humiliated that I couldn’t rise about my station as a deadweight. So I go home and do research. Research, it turns out, is mostly videos of ripped men flapping their legs in the waves and doing Kegel exercises by the poolside. I mimic their arm movements and breathing patterns as I eat potato chips in bed. Somehow, I even go to the gym. I lay out on the flat hard cement in a humid city basement. When I’m on the yoga mat, I have this image of an excavator rolling across my body, flattening all of the ridges and lumps until I’m smooth like one of those rocks that skips easily across the water.

And then I do actual practice. In the early evenings and dead weekend mornings I go to the pool, slipping first into the shallow end. I hug the ledge, just as the toned online men told me to do, and then I slowly lift my legs out, tuck my hips up, imagine the water filling up my belly button like a cenote. I take a deep inhale and let myself go. At the beginning I lightly kick my feet like the paddle wheel of a steamboat. For a second and a half I truly am floating. I get it, I get it, Hallelujah, a-men. But then I start to sink again. Ass first, the legs going down. An old Greek man looks at me and politely chuckles. I am no nearer to God, it seems.

I roll out of the water and sit on the stone steps that rise from the poolside. There’s the bridge, and then the other, and further south the big buildings downtown. The river snakes north, the sky turns from light blue to dark blue to bruise-purple after the last of the pink and the orange. The yellow lights dangle in the grass and the trees, followed by the screech-screech-screech of crickets. Bats dart around the glow of the lampposts. It’s here where I wonder, frankly, God almighty, why am I doing this. What am I trying to prove, who am I attempting to disprove? It just feels silly. Better than being on my phone, I guess. But that’s not saying much. On the river the city ferries churn north. Police boats follow, with their blue and red lights. And then come these long, flat barges with nothing visible but a lone light or two. They look like rafts out there with little lanterns. The river, the lone boats, the nighttime. The realization is so sudden and simple that I get annoyed with myself. Stupid, silly man, I think. All this time I thought I had been doing something innocuous, fun, lighthearted, completely original. But it had all already been done before. I was trying to be baby Moses in the basket, yes, that’s that part of it. But the river, the lights, the steamboats, floating far far away. All that time I was preparing for Huck and Jim.

⁂

NOTICE: PERSONS attempting to find a motive in this narrative will be prosecuted; persons attempting to find a moral in it will be banished; persons attempting to find a plot in it will be shot. – The Author

(Mark Twain, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn)

There are books that are so powerful, so all-consuming, that I can’t pinpoint precisely the imprint they leave, because the impact is so massive that it takes up my whole life. The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn is one of those books. It is a strange, deeply flawed, but beautiful book.

The book is about Huck Finn, a rebellious (but confused) kid in antebellum Missouri. After being tormented by his abusive and neglectful father, Huck decides to sneak away. He hides away a raft, and then sets off on the Mississippi River. While camping out on an uninhabited island he comes across Jim, an enslaved man who has also decided to run away. Realizing that they both escaped on the same night, and that Jim will undoubtedly be seen as guilty for Huck’s ‘murder’, they both decide to stick close. At first their connection is tense, and uncertain. Huck Finn can’t entirely see Jim as a full person. Jim is anything but free with Huck: Huck could at any moment decide to sell him out and down the river, just as many other whites would do. Yet Huck and Jim share these beautiful meandering conversations while they float along the Mississippi. If you can get past the unwieldy and, frankly, racist language that’s peppered throughout, you’re rewarded with a glimpse of a better world, of two people who should be oil and water somehow slowly refiguring out the entire world together.

Huck is a deeply intuitive person, and his intuition is almost always on the right path. They decide to keep taking the raft south on the Mississippi, and then sneak Jim into the town of Cairo1 on the southernmost border of Illinois, a free state. From there he can be a free man. It’s what seems right to Huck. It’s Huck’s schooling, however, that wants to betray him. While on the raft he vaguely recalls sermons and lessons about stealing, and sin, and since Jim is legally property, Huck convinces himself that he is doing something wrong by helping Jim. All the while Jim is sharing how desperate he is for freedom. Jim tells Huck that when he gets to the free states, he’ll save up every penny he earns so that he can buy his wife out of bondage. And from there, they can work and save up to free their two children as well. It shakes Huck, but there is still this powerful undercurrent of conformity that betrays what he feels and knows to be right.

Onwards they float towards Cairo. Jim looks at the lights that he sees on land and wonders, always, if it’s finally Cairo, while the thought fills Huck with dread. He wants his new friend to be free. He knows it’s the right thing. But he doesn’t want to make the decision. He wants it made for him. And he gets his wish. In the middle of the fog one night a thundering noise comes across the water. They see it’s a steamboat, heading towards them,

“Looking like a black cloud with rows of glow-worms around it; but all of a sudden she bulged out, big and scary, with a long row of wide-open furnace doors shining like red-hot teeth… and as Jim went overboard on one side and I on the other, she come smashing straight through the raft.” The only decision that matters now is sink, or swim.

⁂

The prevailing image of The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn is of the two figures on their raft, with the great Mississippi beneath them. That’s because it is a beautiful and hopeful image. But the book is really a land-based story, and the shore is littered with shipwrecks. Huck and Jim are repeatedly thrown into the lives of people who are hopelessly, desperately lost. They jump from one hopeless situation to the next as the raft drifts further away from the hope of Cairo. It was the kind of thing that was maddening to read as a kid. ‘Just go North! Get back on the raft,’ I’d say, ‘quit dealing with these idiots!’ Well, I’m sprouting my first grey hairs now, so I finally get it. It is almost impossible to stay on the river. Life conspires to thrash us back to shore.

Huck shacks up with a family caught in an eternal and pointless blood feud, who eventually all murder one another in a mass shootout. Another family lives a life of leisure, and slave-backed comfort, but is caught in endless mourning over one of their daughters that died too young. As the raft ventures further South, it only gets worse. All around are these stately homesteads and plantations, yet everyone inside of them is hopelessly lost. These are the winners of society, yet there seems to be little joy. It’s like they are stuck there, forever being punished for some great sin they have committed. And that’s exactly the case. Because they are all in hell.

⁂

Huck and Jim’s trip on the Mississippi is not all that different than other ‘descent into hell’ stories. Joseph Conrad takes us on the Congo River in The Heart of Darkness. In Dante’s Inferno, Alighieri is led through the different layers of hell by the great poet Virgil. In a way, Huck Finn is almost a Dante character; he is ignorant of an essential thing and needs to see it directly to believe it. And we see hell through Huck’s and Dante’s perspective, not Virgil’s or Jim’s.

Two characters really embody this descent into American hell perfectly. While on the raft Huck and Jim meet two men. When they get around to introducing themselves, the men aren’t willing to admit who they actually are (just sad, poor men down on their luck). So instead one of the men decides that he’s a Duke, shipwrecked in America. Not to be outdone, the older man says that he’s actually the Dauphin of France, the son of the guillotined King Louis XVI. Of course, they begin to really believe their own lies. The Duke, deciding all of the sudden that he is a great writer and actor, decides that their next get-rich-quick scheme should be to put on a play in the nearest town. They cobble together a play out of the little bits of Shakespeare they can remember, which leads to a brutal butchering of Hamlet’s soliloquy. But when they only get a middling reaction from the audience, the King and the Duke decide to instead ‘dumb down’ the play and turn it into a vulgar comedy. They take out all of their mediocre art, and churn out something worse: a nothing play, which they even call The Royal Nonesuch. On the first night the townspeople seem to love it. But on the second night, while Huck Finn lets people in, he sees that everyone is carrying in fruit, produce, rotten cabbages. The crowd has turned on the King and the Duke. It’s a damning, scathing indictment of the kind of person who would butcher art, and produce ugly content and slop, out of a desperate desire to get ahead at all costs.

But after all this, it was not enough for the King and the Duke to betray themselves, and then the art they enjoyed, or the people they performed for. They eventually turn to betraying the others on the raft. Not satisfied with selling themselves, the King and the Duke grab Jim and sell him down the river, to another slaveowner.

⁂

In the beginning of this letter, I started with a quote from David Foster Wallace. It works because of the context (water, staying afloat), but also because of the man. For Wallace and all of Generation X, there was almost no greater sin than ‘selling out’. If you sold yourself, you were no better than ‘the man’. You were a phony, a fraud, another empty suit from the corporate world. I was not immune to this message. I was raised by parents from Generation X, who are good people that probably passed this fear of selling-out down to me in some way. I also lived in rainy Seattle during the sad whimpering death of the grunge dream of the 1990s, where the ghost of Kurt Cobain with his shotgun still lingered. But it feels quaint to bemoan selling out nowadays. Much of the modern economy is quite literally about spinning yourself into a product to be sold, and handled, and gawked at online. It’s probable that you found this letter through some mechanism of self-promotion on my end, in which case: thanks! But also: I am very sorry, Kurt Cobain, for in any small way pushing us closer to your nightmare.

Selling out is an interesting concept, but at its heart it is a much older fear; betrayal. Specifically a betrayal of oneself. Selling out is not all that different than ‘selling yourself short’, of seeing and sharing less of yourself than actually exists. In the case of Generation X, especially for someone like Cobain, the fear was that selling out was a betrayal of how someone truly was. If a person was willing and able to sell themselves – so the story goes – then there’s absolutely no limit to what else they could sell. They could betray communities, loved ones, their political beliefs, their art. There was no limit, because selling oneself stems from radical egoism. If you work from the place of believing that you and you alone are the most important thing that must be promoted, then you will go to any length to see yourself rise above the heap, including by destroying your true nature.

Huckleberry Finn is full of betrayers, as we’ve seen. The father who betrays his son through abuse. The small ways that Huck betrays Jim by belittling and gaslighting him on the raft. And then the King and the Duke, with their snowballing betrayals, which leads to Jim’s enslavement.

I recently revisited Dante’s Inferno for the first time since high school. The descent through the different layers of hell takes us through familiar scenes and senses; fire, screaming, eternal wailing, torture! Loud misery abounding! Classic hell stuff! Each time I’ve read it, I thought that the final layer of hell would be a somehow infinitely louder and smellier and nastier version of the earlier layers. But when they reach the ninth and final layer of hell, Dante and Virgil don’t see fiery pits of despair but instead a massive frozen lake known as Cocytus. Scattered across the water is a field of people frozen in the ice. Many of them are frozen in such a way that they’re forced to spend eternity staring at their reflections in the shiny surfaces in front of them. Each teardrop that they spill slowly builds upon the water. And the ice numbs them entirely. They can feel nothing. The sinners in Cocytus are completely disembodied. They only have their thoughts of eternal regret and shame.

It is such a stark and terrifying image that I always imagine the sin they’re being punished for is violence, or heresy. But no, the most despicable sin in Inferno is betrayal, specifically betrayal of people they had ‘special bonds’ with. All of the souls in Cocytus betrayed someone dear; loved ones, friends, communities. And as punishment they’re forced to freeze eternally in a place without love, without warmth, with nothing but their sad little reflections staring back at them.

⁂

Back in April, I wrote a long-winded letter that was essentially about me trying (and somewhat failing) to break the ice in my life. I had felt frozen and disembodied for months. The culprit was in some way just depression, and boring old sadness. But I had also felt increasingly frozen to bad habits, specifically to digital distractions that were only making me feel even more alienated and unalive. I wanted to describe what it felt like for me to be addicted to screens. The metaphor that I used at the time was that of the slot machine. I do think screens and the internet are these little machines that promise big hits, and wellsprings of meaning, and occasionally there are jackpots that make it seem worth it. In gambling, famously, the house always wins, and many more lives are destroyed than made.

But lately, it’s felt like there is something much worse in my pocket than a slot machine. I go on these digital benders where I hold up this glass block in my hand for hours. The time seems to lose all shape. My body starts to lurch forward. The screens seem to answer to me, like they bend around me and try to capture what I really want, and how I really am. I know in my heart of hearts that I don’t want clips of video game playthroughs, or contextless threads of obscure internet feuds, or marketing disguised as writing. But still I scroll, and scroll, and scroll. Because it's addicting! Because screens, and most of the internet at this point, lure a person in by convincing them that they can be adequate replacements for the entire world. Because life is scary, hurtful, confusing, and the screens promise a limitless expanse of controlled experiences. It is not really the full world, but it warps my body and brain in such a way that I end up so beaten, so tired, that I can nearly come to believe that it truly is. This stupid phone in my pocket is a small shard of Lake Cocytus. The ninth layer of hell. Some kind of cosmic punishment for having betrayed the gift of life. Punishment for having retreated so far into myself that there is nothing left to look at.

When the addiction gets its worst, there’s always some breaking point. I liken it to some candle deep inside, sputtering as the flame reaches the end of the wick. I end up thinking, ‘this is really the life’? All of the universe, all of history, all of everything has led to this moment where it’s desirable to escape life, to crawl into ourselves, to waste away in digital graveyards that are only pale imitations of the real and colorful life? This is what we want? This is the beautiful world that we were promised?

⁂

Floating across this essay now is the image of our digital prison as hell. But it doesn’t hold water. There it goes, sinking away. Hell is ostensibly a real place. The internet is not a place – it is a bundle of wires. Hell is where people, sinners, deserve to go for living with wickedness. The internet is not created by God, but by people – specifically dull people who are willing to sell all of humanity down the river. No one, I think, deserves to be punished by the internet. The internet is, mainly, created by people who want there to be a world that exists outside of life. It’s no accident that some of the world’s biggest tech gurus are terrified of dying. They are going to endless lengths to avoid the basic facts of what it means to be an organism. They will fill their raft with gold, and plunder, and endlessly self-optimize every aspect of their lives, but it still won’t matter; their rafts will sink.

But back to the good word of literature, to the raft and the river. Ernest Hemingway very famously said that “All modern American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain called Huckleberry Finn." But he believed the ending was “cheating”. Hemingway thought the book should have ended with Jim being sold back into slavery. I won’t spoil the ending on this 140 year old book, but while I don’t think the ending works as good literature, it is honest. By the end of Huckleberry Finn, it feels like Mark Twain has reached his limits of how far he can go. He was constrained by a readership that wanted closure. Ideally with a happy ending. So Twain panicked, and went with an ending that wasn’t realistic, but still had some good lessons in it. The ending was a lowercase-b betrayal of the kind of honest art that he believed in. So it goes. In the great big river Mark Twain started to drown, so he paddled for shore. But we should forgive him for that.

It's frustrating to know that there’s no perfect ending. I’m feeling that right now, as I’m sitting here. To pull off a big ending would be like positioning myself as the old fish in the David Foster Wallace parable. I’m a tiny fish. I barely know what the water is. Even though I’m frozen in it. I have no clear answers as to how a person should be. Occasionally, I get a peek at what it would be like to float. I feel myself floating when I’m trying to corral words and ideas into a tidy pen. I get a flutter above my ribcage when I read something truly beautiful. The joy is effortless when I’m with others that I cherish and love. I sometimes see people who are so completely themselves, happily living their lives, and to me that’s heaven on earth.

In the last few hours of writing this letter, I went to the river again. There were the bridges, the beach glass, the geese all grown up. There’s this line from Twain’s The Adventures of Tom Sawyer that I’ve never forgotten. “The sun rose upon a tranquil world, and beamed down upon the peaceful village like a benediction.” It was dusk when I was at the river. The sun was setting, but it looked like an orange communion wafer being held in the sky above the altar of the horizon. The beautiful benediction. There were some kids running along the pathway. Friends posed in front of the sunset. And then someone came up to the edge of the path. They grabbed the railing, and stood so that they were being held by the metal bars. They had earphones in, and closed their eyes, and smiled, and slowly moved their lips. Once the sun was gone, they turned back from the river and walked up a small hill at the base of the bridge. They sat in the grass, cross legged. The breeze picked up and they held their arms up, and slowly bent to the left, and then over to the right, moving like cattails in the wind, like waves on the river. They looked out, and smiled. That’s how I would like to be.

I am deeply saddened to report that it is pronounced ‘Cay-row’. If you have any issues with this, please take it up with the State of Illinois.

Hi Michael!

You don't know who I am, but this piece deeply touched me. I could say a lot about it. Thank you so much for writing it! I have been thinking this lately; that my phone (or really, the internet, in a lot of ways) is more then addictive, that it is some cosmic test or punishment: that my life, in some important way, is being stolen by a force that sneaks itself back in no matter how hard I try. So thank you - I really appreciate it.

Michael- I love references to classics. And I haven’t revisited Huck Finn in some time. A great reminder. Hope you’re well this week? Cheers, -Thalia