Refaat Alareer: A Writer Killed in Gaza

Reflections on the Palestinian writer Refaat Alareer.

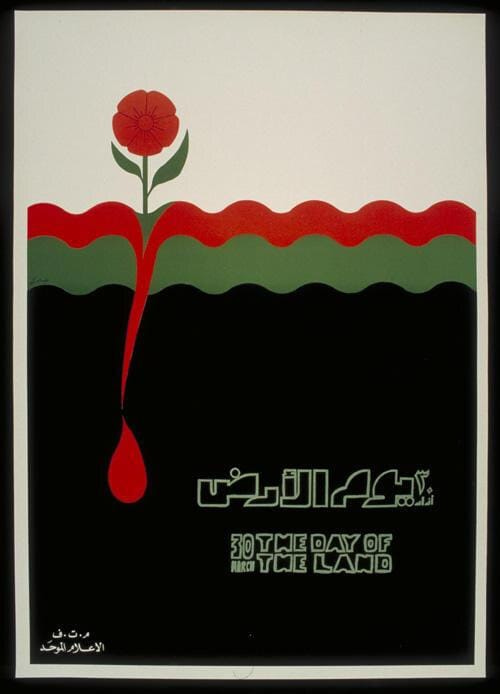

“Land Day – 1985”, The Palestine Poster Project Archives

His beauty shall in these black lines be seen,

And they shall live, and he in them, still green.

– William Shakespeare, Sonnet 63

In 2021, during a wave of attacks that Israel launched on Palestine, Refaat Alareer huddled with his wife and children in the living room of their apartment in the Gaza Strip. Linah, one of his daughters, asked if ‘they’ (Israel) could still bomb their home — the power had gone out in the building after all, perhaps the Israeli jets would not be able to see them?

As Alareer wrote then, in the New York Times,

On Tuesday, Linah asked her question again after my wife and I didn’t answer it the first time: Can they destroy our building if the power is out? I wanted to say: “Yes, little Linah, Israel can still destroy the beautiful al-Jawharah building, or any of our buildings, even in the darkness. Each of our homes is full of tales and stories that must be told. Our homes annoy the Israeli war machine, mock it, haunt it, even in the darkness. It can’t abide their existence. And, with American tax dollars and international immunity, Israel presumably will go on destroying our buildings until there is nothing left.”

But I can’t tell Linah any of this. So I lie: “No, sweetie. They can’t see us in the dark.”

Refaat Alareer, a Palestinian writer and professor, was killed yesterday in Gaza by an Israeli airstrike. He is of the more than 17,000 Palestinians that have been killed during this war, 7,000 of whom are children.

Refaat’s great crime was that he was a writer. He co-founded We Are Not Numbers, a nonprofit that provides English-language writing workshops for young people in Gaza, and he edited two short story collections by writers who have experienced the traumas of warfare firsthand; Gaza Unsilenced and Gaza Writes Back. He taught world literature and creative writing at the Islamic University of Gaza. He counted among his literary influences Shakespeare, John Donne, and George Eliot, among others. He taught and wrote in English because he knew that it was the only language that would capture the attention of those in the world who needed to hear his stories, and the stories of Palestinians, the most.

Us, essentially. He wrote for us.

Words. Words. Words. As Hamlet says. Language is all we have to voice our struggle and to fight back. The words are our most valuable treasure that we ought to utilize in order to educate ourselves and educate others.

He was still writing as this war began. In October, he wrote about his home being struck by Israeli airstrikes.

Right before the strikes, I heard a rumble that was unusual. And without any warning: Boom! It was so close. Boom! I felt myself forced back against the wall. The building shook. Smoke. Gunpowder. Debris. And Screams. Men. Women. Children… Instinctively, the kids ran for their lives. Some, though, — like little Eman, 6 — were unable to move fast. Eman had already been injured in a bombing last week. She has platinum in her left leg… We do not know why the building was targeted. My mother-in-law insists it is because I talk to the media. Israel has now killed 16 journalists over the past two weeks. My mom also raised the same concern, “Do not write stuff online, my son. You know what I mean,” she implored.

But still, Refaat kept writing. As of a few weeks ago, he wrote about himself and his family being sheltered in a hospital, along with hundreds of others. He wrote of the imposing sight of Israeli tanks parked outside the building, and the fear that was gripping everyone inside.

Almost everyone around me has a high temperature, a headache or an upset stomach. Many of Gaza’s hospitals and clinics are now closed. We fear that Israel could prolong the genocide. What happens if the tanks remain in Gaza for another month? Or two months? Or even more? The mere thought of a prolonged genocide terrifies us because nothing kills like hunger.

As far as I can tell, the last thing that he wrote was a brief tweet, on December 4th. It was a quote-tweet of a video of American Vice President Kamala Harris, assuring the public that “Israel has a right to defend itself.” To that, Refaat wrote, “The Democratic Party and Biden are responsible for the Gaza genocide perpetrated by Israel.”

Three days later, he was killed by Israel.

Still, literature has the ability to educate us, to heal us, to bring us all together, and to open up new possibilities of a better future. Literature has the ability to create bridges and reach out to all. That is why people who read and appreciate literature tend to be more thoughtful. And that is why totalitarian regimes hate literature. In the oppressed societies, literature is usually connected with their struggle and fight for human rights and justice. Literature becomes and is resistance.

Refaat’s work, in many different ways, shined a light on the brutal horrors of life in Gaza. The people that he wrote about were not just statistics in a death-count, or faceless victims: they were real people, with round and full lives — lives of complications and beauty that were needlessly cut short by war. And now Refaat is dead. Hundreds, likely thousands more, will die in Gaza. And many of them, in the last moments of their life, will be writing text messages, essays, farewell notes, tweets — often in English, directed at the readers out there who need to listen. The vast, shapeless us.

In one of his final video interviews, he spoke about the onslaught and the despair that he and so many others in Gaza have felt during the war. In the video he is crying, struggling. Yet he’s defiant, and courageous, as he explains just how far he will go to defend what he believes in.

And I was telling somebody, the other day, that I’m an academic. Probably the toughest thing that I have at home is an EXPO marker. But if the Israelis invade, if they barge at us, charge at us, open door-to-door, to massacre us, I am going to use that marker, throw it at the Israeli soldiers, even if that is the last thing that I would be able to do.

Refaat believed in literature, and in writing as an act of resistance. He did not hide behind his words. He did not turn away from the terrors of the world. We cannot bring Refaat back from the dead, just as we can’t bring back the 17,000 other people killed in Gaza and the West Bank. But we can do what writers do: share stories, protect them, and keep Refaat’s voice alive in the ways that we can. So long as his words live on in the black lines of text, some part of him will survive. That is the fundamental moral obligation of art, and literature, and culture: to keep the dead with us, and hopes of a better world alive. We owe it to Refaat. We owe it to the hundreds and thousands of others who have been killed in Palestine for the simple crime of living.

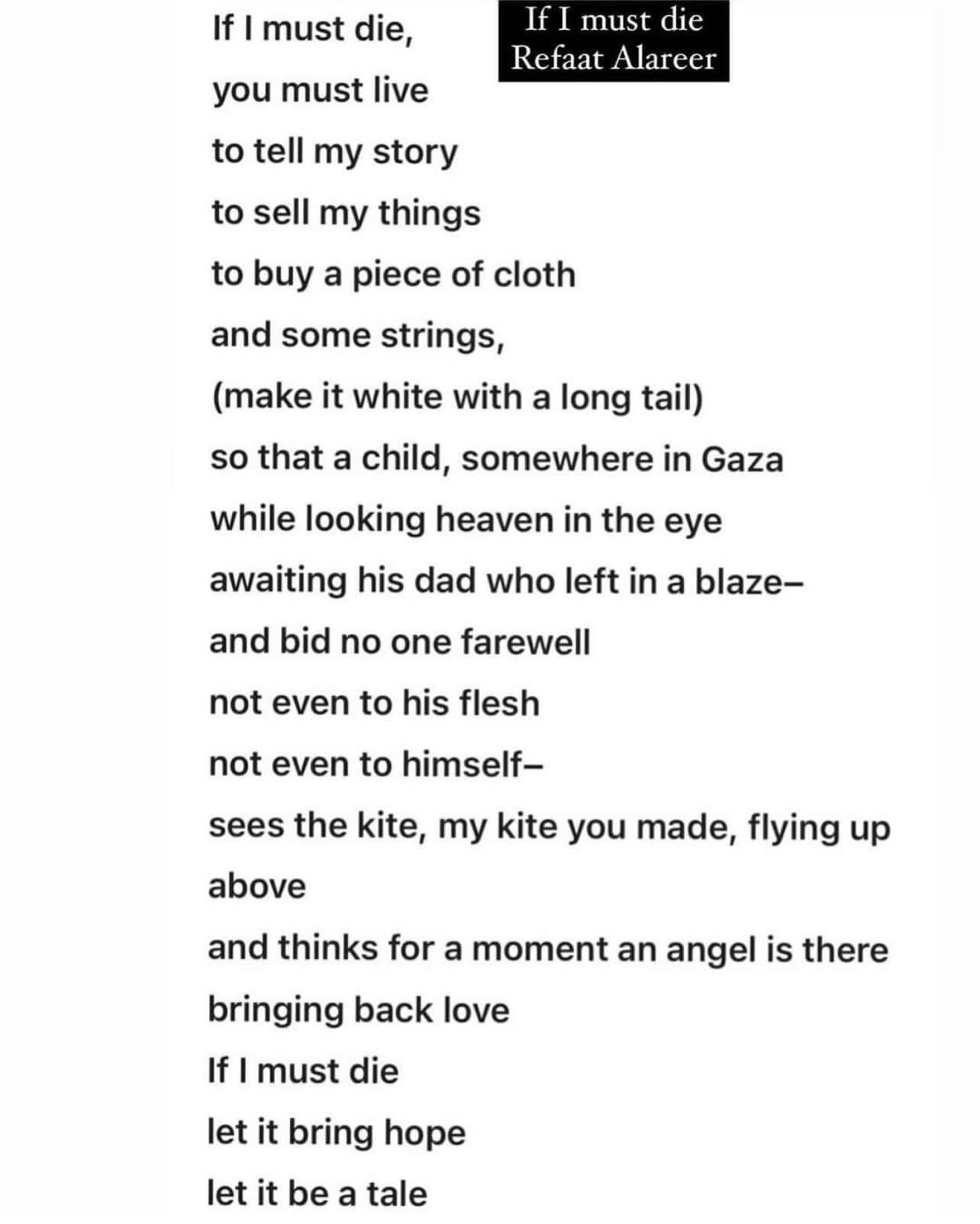

I close with a poem that Refaat wrote on November 1st, titled If I must Die.