Are there larger things than Independence?

What is independence, and is it what we need right now? Thoughts from Iceland, and Halldór Laxness’ Independent People.

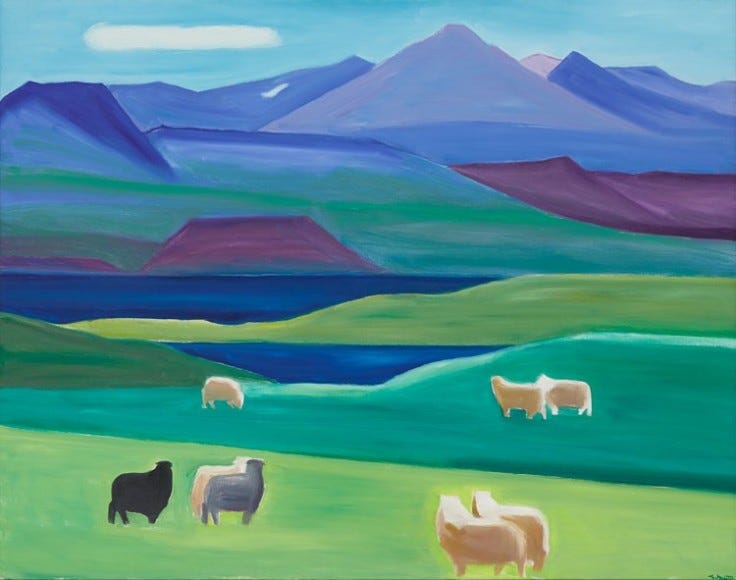

It is easy to dismiss a tiny island caught between two great continents. But I have a special fondness for a little nation called Iceland. It is such a deceptively simple country. Its name is cold, but the land is warm and rich with green grass and heaths. Its geography is marked by massive mountain ranges capped with snow, but underneath lurk fissures of magma and steam that erupt in violent oranges and reds. Flowing from the mountains are plains of ash and debris, yet in some of the black basins are pools of light-blue water heated with volcanic energy, where people swim and float and hold one another. For miles stretch fjords and gulleys of harsh stone, yet the locals claim that within the moss-covered boulders are fairies and elves, or what they call the Huldufólk — the hidden people. And everyone you go in Iceland you will find its famous sheep. In the winter the sheep trudge lethargically through the mud, or wait quietly in their pens for the first shoots of spring. But in the warmer months they trot through the grass and over the countryside, filling the fields and the roads and the valleys of green. In the warm days they climb the mountains, and from the cliffsides they bleat and slowly drag their hooves. For a single moment these obedient creatures, bred and caged exclusively for their meat and wool, slip past the farmers and gather in a place where they witness the whole world and see everything. It is only appropriate that one of the world’s great books is from this little country, and mostly concerned with the simple lives of sheep.

Halldór Laxness’ Independent People is a strange but wonderful book about a small farm in quiet Iceland over a century ago. The sheep farm is headed by a man named Bjartur, who is bullheaded and steadfast in his isolation. He is the type of person who has winter in his heart. He is cold and cruel towards himself and the world, but he is full of contradictions and occasionally radiant warmth. He is a businessman, but in his spare moments he walks through the mountains and recites poetry to himself. He is often cruel to his children and family, yet will kneel in the pastures and lick the grass so that he can view the world briefly from the vantage point of his sheep. He is distrustful of flowers and the onset of warm weather, yet he names his homestead Summerhouses. What is there to do with a person like Bjartur? There is something wrong with him. Possibly many things. It seems that the fields of his soul are fallow. Nothing good or beautiful can grow there. The novel hinges on a deceptively simple question: can a person like Bjartur, who is cold and zealously assured of his independence from others, ever cultivate the seed of something generous and beautiful?

People like Bjartur are everywhere. He is in our workplaces, our front offices, and our governments. The Iceland of Independent People is littered with men like him: farmers, shop-owners, all of them missionaries of a religion called 'independence'. They take what they can from society, and then cast themselves far away. If they are successful, then they sing the praises of their own brilliance and independence. If they fail, then they blame the rest of society for spoiling their dream. That is Bjartur. But there is also more to Bjartur than that. When I picture Bjartur, I think of some of the trees that one can spot in higher elevations. In alpine and sub-alpine biomes in the mountains the treeline eventually ends, but far up from the forest edge a person can still spot lone trees, resiliently growing alone. These trees, called the Krummholz, will often be horrendously bent and misshapen from wind and snow. Their bark is often flaky and dark, and their trunks will curve inwards or out as if they were permanently hunched over. A tree like that is just like Bjartur: weathered, aged, hardened by the cold, broken by his own ambition for independence.

But is a person like Bjartur even completely independent? It is not like he is the first person to decide to move to nature and keep some sheep. He is only one of thousands following the zeitgeist in the hopes of making oneself an entrepreneur. But even with his humble farm and house, he still pays rent on the land to the local bailiff. He can be profitable, yet his ability to eat is still determined by the demand of wool and meat in far-off cities. Bjartur wants to think of himself as a man free of society, yet it is society's medicine that protects his livestock from crippling disease. What could it possibly mean, then, to be independent?

Almost never questioned, however, is whether 'independence' is worth the trouble. Bjartur's independence is only possible through frigid cruelty towards his family and neighbors. Even as he slowly accrues more profits, the benefits rarely go to actual people. In the boom years he increases his sheep, yet still feeds himself and his family a measly diet of dried fish and gruel. Slowly the reach of his farm begins to expand outwards, yet Bjartur rarely tells his children of the world beyond it. It is a bleak, cold life. The life of independence is dull and unremarkable. To make it in a world like this is to permanently keep one's head down, and to push one's thoughts and doubts away whenever they arise.

Can a world of complete isolation ever be good? Can independence ever be beautiful when it depends on diminishing everything in a person's life that is not immediately useful? There is something so alluring about the surface of Bjartur's life. A simple home with some land in a lush green valley. One could mute out the noise of the loud world beyond. One could slowly accumulate a pasture of beauty, tinker away at one's craft, and build something like a life. A life of complete and total independence. It would not look all that different than the world of an independent Icelandic farmer. But can such a life be truly good and beautiful?

It is easy to read Independent People and place all of the blame for this miserable life at Bjartur's feet. He is a cold, cruel, and stupid person — he of course deserves much blame. Our society loves to heap all of our woes of society and history onto a lone individual. It is tempting to look at Bjartur's life and imagine what would be different in Independent People if he merely made a few minor adjustments. Maybe if he was a tad kinder, or slightly more generous, then perhaps he would not be living his wrong life. He could be polite, genteel, and more of a character that one could get behind. Maybe then one could really empathize with him, and not be instantly repulsed. But maybe there are bigger things that need to change than individuals. Maybe, perhaps, our obsession with independence. But it is so nice to be independent. Or to at least think of oneself as independent.

What makes a novel like Independent People so powerful is that it quietly lures you into its world, until one's thoughts on the book are indistinguishable from one's reality of daily life. This was only my second re-read of the novel, but it gripped me this time around in a way that I did not anticipate. By the beginning of March, I had begun to see Bjartur everywhere. I saw him in the shop-owners at the market stalls, the faces of the cops as they proudly gripped their belts, and even the people at the cafes as they furiously typed lines of code into their laptops. There were times when I was alone at home, working or writing, when I would feel the cold spirit of Bjartur move within me. I would be rearranging words on a page, feeling as proud as Bjartur as he herded his flocks. Look at these little sheep, I would think. The words are obeying me, as they should. Look at me in my studio, with my stacks of papers and pens. As long as I have this, I am an independent person. And I would open my laptop and watch my numbers go up, and what would follow were elaborate plans of what I could buy and place around my rented box to show that I was an independent person. And on one of these nights I made a fresh pot of tea, inhaling the fumes as I sat at my writing desk, while just below the window the scream of a banshee wailed in the alleyway. It was a woman in a tent, or a man pulling a cart of his belongings from the methadone clinic. I looked out the window and thought, for the briefest millisecond, 'At least I am up here and not down there,' and that flash of coldness made me want to hide under the table and cry in shame — shame at the awareness that I could ever think such a thing and be so removed from others, and shame that some part of my soul was still so frozen like Bjartur's.

There is something deficient within the independent person, yes. But there is something deeply, irrevocably wrong with the whole mindset of complete independence. Bjartur is dumb, and harsh, and naive, but he is only a pawn in a much larger game. He is a sacrificial lamb to a societal push to rip civil society apart. It is possible that he even knows that he is a martyr. But he wants to be a martyr, because he believes that this is his cause — even though he has had no say in defining society’s idea of independence. It is not in his interest to question things too far, or to bite the hands of the owners that dangle the threat of debt over his head. And yes, sure, there are rumors of new theories in cities such as Reykjavik over how society should be collectively organized, but why would he bother? After all, he does not need other people. He does not need society, or God, or even the fairies of Icelandic myths. His world is one where, as Laxness writes, "Sensible people don't like things to happen." The independent farmers trudge through the fields, shepherding their sheep, endlessly repeating their mantras of independence, and all the while the people of vision, such as the women and the children, watch from the homes and can see quite clearly that the independent people are not independent. The independent people are barely even people. They repeat the same actions over and over, as if subconsciously. There is no aim to their movement, no higher goal, no purpose. The men have craned necks, and dimensionless faces, and float upon the worlds as if they were ghosts. It is like the independent people are already dead.

There are phantoms lurking in the minds of independent people. A spectre is haunting this small island in the North-Atlantic. In Bjartur's land there is folktale of a spirit named Kolumkilli, who haunts the farms and causes havoc to the goals of independent men. The sheep spend no small part of the novel terrified. They bleat wildly in the evenings. At bedtime the children share tales of seeing bright red eyes in the darkness of the barn. An independent man such as Bjartur cannot believe such a thing. But when the wails of the ghosts become too much, even the independent people begin to fear. Maybe there really is something out there beyond one's control. Perhaps our money and roads and religions of commerce cannot sweep away the old ghosts of the past. Fear turns into doubt. Doubt becomes a wedge that allows other ideas to sneak in. The old ghosts are a reminder of past truths, past lives — of worlds where complete independence was neither possible nor noble. And one day the children are working in the yard when they see a spot of color in the ground. It is a dandelion, the first flower of many months. The spell of eternal winter begins to crack. The terrible coldness will not last forever.

That is what I have had to tell myself, again and again recently: It will not last forever. It will not last forever. I am looking for dandelions. Signs of life. Momentary glimpses of fire and warmth. Few of my dependable mantras have worked, and so I have begun to doubt so many things. But the doubt has opened a wedge. Something else is slipping in. What it is, I am not precisely sure. But it is something ancient. Irrational. Fantastic.

I am seeing signs and flowers everywhere. While writing this letter I went to a diner, desperate for some food and a warm bottomless mug of coffee to hold. When I sat at the counter I looked up at the television and saw a looping video of scenes from Iceland. It played for the whole breakfast as I sleepily recounted the places I had been. Later that afternoon, at a cafe here in town, the first thing that the radio station played was a song by Björk. I have had the feeling of hands resting on my shoulders, pointing me in the direction of where I ought to go. They are holding me still, I think. They are keeping me here. Perhaps they are simple, boring angels — or Icelandic fairies. And they are pointing me here.

Maybe this is seeing signs where none exist. Like seeing Jesus' face on a piece of burnt toast. Perhaps these are merely small consolations of a sad, terrified person. But if that is the case: who cares, so what? "The soul of man needs every day a little consolation if it is to live," so writes Halldór Laxness in Independent People. My small consolation is a belief that we are occasionally guided towards what we need.

Independent People is a book of winter. For that reason I find it hard to convince many people to read it. 'Too cold, too bleak'. I can understand those reactions, especially now. But when the first signs of warmth spring through in this novel, it is glorious — just glorious. The prose is of course stunning, and so is the translation by J.A. Thompson. But what makes the novel work is that it is brutally honest in its frigidity. When the warmth arrives, it is truly earned. When a flower emerges on the page, it is a small revelation. When the children's eyes light up after their first taste of fresh milk, you can taste how sweet it must be. When a mother sits her child on her lap and tells him that he is destined to sing the most beautiful song of the world, you can truly believe such a thing.

There is a wonderful scene where a stranger visits the farm. He brings with him a large book, which Bjartur's children have never seen before. The book, he says, contains stories of whole nations and peoples that the children have never heard of. The children crowd around the book as if it is a holy object. The children are each, in their own ways, changed for life. For a moment we are given a glimpse of the holy power of great literature, and how it can melt the winter in our hearts and spring us towards something far larger than ourselves. Why else still bother reading?

I suspect that my reading life, to the extent that such a thing still exists, is powered off the fumes of having first experienced, as a child, the transformative effects of great literature. Adulthood has been a long and uneven attempt to rekindle that spark. It has often not worked. There have been many good books, and great lines or passages that have somehow stuck in this tired brain. But there have been few books that have completely ruptured and reordered my entire existence in the way that I secretly crave. I want to be casually upended and destroyed by the books that I read. At some point, I thought that such a thing could not happen as an adult. I convinced myself that all I could do now was moderately enjoy books, but not be completely and irrevocably changed by them. Independent People, fortunately for me, is a transformative book. It is a special book, a holy book. I still don't know what to do with holy books: give thanks, and pray? Here I am, giving thanks and praise.

A person is incredibly lucky if they ever discover a book that will change their life. They are especially fortunate if such a book is given to them at precisely the right time that they need it. Two years ago, on the tail-end of a wonderful trip to Iceland in the winter, full of joy and warmth and love with another person, I walked into a bookshop in Reykjavik and picked out a book at random. It was Halldór Laxness' Independent People. I would like to believe that in such a cold world, I was guided towards this book, by angels or fairies. In such an even colder world now, I find myself needing to cling to small magic and miracles. It is so cold here, and I am so tired of winter. I am wearing my hat made of Icelandic wool, and wishing that I was somewhere else. I wish that I was gliding across the fields of Iceland with everything beautiful ahead. I wish that I was floating and being held in the warm waters of Iceland. I wish that I was once again something far larger than an independent person.

"I want to be casually upended and destroyed by the books that I read."

i love that sentiment. just read sarah chihaya's 'bibliophobia' in which she writes about her LIFE RUINER - the book that shook her so profoundly that completely changed her (and, for a while, ruined books for her because nothing compared in force, magnitude or connection). i felt so jealous because i don't think i have had that experience yet.

this book sounds wonderful, i love sad and bleak. and i love iceland. i will definitely look for it.

I am in awe of how romantic you manage to make this book sound! I personally love this section;

"Bjartur is dumb, and harsh, and naive, but he is only a pawn in a much larger game. He is a sacrificial lamb to a societal push to rip civil society apart. It is possible that he even knows that he is a martyr. But he wants to be a martyr, because he believes that this is his cause — even though he has had no say in defining society’s idea of independence. It is not in his interest to question things too far, or to bite the hands of the owners that dangle the threat of debt over his head. And yes, sure, there are rumors of new theories in cities such as Reykjavik over how society should be collectively organized, but why would he bother? After all, he does not need other people. He does not need society, or God, or even the fairies of Icelandic myths. His world is one where, as Laxness writes, "Sensible people don't like things to happen."

because it is so true - Bjartur is an idiot, but this idiocy is not born from him alone, it is a response, to a wider message and a large shift in humanity and society. I think that clicks about half way through the novel, after you've gotten all the inital shock out the way of how Bjartur only wants to eat fish forever and ever and live in squalor, that Bjartur's belief of independent hedonism is just a response to the systems that we are made to live under. And then it becomes a different book almost entirely, one that is almost sad, in the way it suggests that how we're living is ridiculous, it's making people sadder, making them punish their children to eat the same fish forever (lol) in the name of a concept that does not mean anything once you're 10 feet under. And he gets there in the end, imo, by the end of the novel. But it is so painful to watch him work it out; and perhaps that is just a fable for us. Would it be worth it to live a life so obsessed with being an island, fiercely independent, only to realise when you're nearing the end that it doesn't amount to what you were told it would. A life interconnected with other humans isn't as horrific as we are told it is, and really it's frankly all that matters, but you can't go back and change it if you've spent your whole life make yourself an island!!

You should read The Colony by Audrey Magee - I saw Petya recc Clear which is good! But I think The Colony is a more fleshed out version of it, with a bit more philosophy about what community and humanity means, which I think you'd enjoy.